Nonviolence has many faces in Palestine, but the most fundamental act of nonviolent resistance is probably the simple act of staying put. I’d like to share with you the stories of three families who resist the military occupation of their land by staying in their own homes and on their own land: the Anastas family of Bethlehem, the Nassar family of Tent of Nations near Bethlehem, and the family of Hani and Rema Habuhaikal in Hebron.

What each of these families has in common is that Israel and/or its settlers want their land/house. The Anastas family lives in their family home housing three generations and their businesses on what was once a busy thoroughfare in Bethlehem. In 2005 Israel built a nine-meter high concrete wall in Bethlehem that surrounded their house on three sides and cut their street off from traffic. Below is a photo taken in the early days after the wall was erected.

I’ve snapped a photo (below) of the Bethlehem map that shows the incursion that the wall makes into Bethlehem land in their area. Israel annexed Rachel’s tomb which is on Bethlehem land with plans to build a settlement nearby. They offered the Anastas family a handsome sum of money to sell their property, but Johnny and Claire believed it was their right to stay in their home. They believe that staying is the most important way they can struggle for the rights of their fellow Palestinians. They operate a travel hostel in their home and a Christian gift shop featuring religious olive wood carvings.

Johnny moved his brake shop for cars to another street in Bethlehem so that he could attract more business. Recently the Israeli military entered his shop, took the machinery he uses for grinding brakes, and shut down the shop with a sign alleging that the owner was making weapons in the shop. Two weeks later Israeli military officials admitted that they were mistaken. Johnny asked for his machinery, but was told it was destroyed and he would have to sue for compensation. The suit may take three years to resolve. In the meantime, Johnny is deprived of his livelihood. The action puts pressure on him and his family to vacate the house and leave it to the Israelis. The Anastas family is determined to stay.

From Bethlehem we made a drive to Tent of Nations, the environmental and educational farm belonging to the Nassar family. The drive would have been shorter, but the direct road to their farm has been blocked by the Israelis forcing the family and their visitors to take a longer and more difficult route through the narrow streets of the small Palestinian village of Nahalin. Why would Israelis want to block the road and make life difficult for the family? Take a look at the map below for clues.

Tent of Nations is at Daher’s Vineyard near the center of the map. Surrounding Daher’s Vineyard are the Israeli settlements of Bitar Elite, Gush Etzion, Eliaza, Nev Daniel, and Erfatz. Each settlement sits on a hilltop and smack in the center of the ring is the hilltop where the Nassar’s Tent of Nations farm is located. Settlements are attempting to join together into settlement blocks encompassing large swaths of land, and Tent of Nations stands in the way.

Daher Nassar was the grandfather of Daoud, Amal, and Daher who now operate the farm. Their grandfather bought the 100 acre farm on a hilltop near Bethlehem in 1916 and registered it with the Ottoman Empire. The family lived in caves on the farm and cultivated it in grapes, olive trees, and other crops continuously since that time. In 1991 the Israeli government declared the Nassar land and its surroundings as Israeli “state land.” The Nassar family has the documents to establish their claim to the land and have been in court for many years. The history of their struggle is at this site.

In 2014 Israeli bulldozers arrived in the middle of the night and bulldozed 1500 olive trees. With the help of the international community, including Jewish people living in England, 1000 new trees were planted. The Nassar family is determined to protect their family land and at the same time “embody a positive approach to conflict and occupation.” Tent of Nations seeks to “work with others in the local area to lay the foundations for a future Palestine, in the belief that justice and peace will grow from the bottom up.”

Yesterday in Hebron, we spent time with a family being squeezed at very close quarters. Hani and Reema Habuhaikal and their children live in the Tel Rumeida area of Hebron where settlers live in close quarters next door or across the street from Palestinians. Hani and Reema can no longer keep a car at their home, since their cars have been burned by settlers in the past. They must pass through checkpoints staffed by Israeli soldiers to go back and forth into the heart of Hebron. Their car is now parked on the other side of Tel Rumeida where they haul all their purchases up and down steep rocky slopes and long paths to reach their house, passing security cameras and armed soldiers along the way.

Sometimes the power lines or the water pipes to the family’s well have been cut by settlers. On one occasion Hani organized the neighborhood in a nonviolent action to demonstrate their community’s legitimate need for water. They ordered a tank truck to deliver water to the community after the well had been disabled. When the soldiers refused to let the truck pass, down the hill came all the little children with bottles and bowls and pitchers to fill with water and take it back up the hill while major media network cameras rolled.

Hani is a strong believer in using nonviolence to work toward social change. He said he learned about nonviolence when he was jailed during the intifada along with many professors and activists with “huge minds” who held discussions about their methods. He said jail gave him lots of time to think. When an oppressed people uses violence, he says, their actions feed into the hands of the powerful oppressor who uses it against them. He has taught his five children not to hate the settlers or the soldiers and to greet each person with respect. I’ve encouraged him to ask his daughter who intends to study journalism to write down these stories to share with the world. We all need inspiration for ways to demonstrate the realities of oppression without engendering new hate.

That evening Hani’s family invited us to celebrate Iftar, the breaking of the Ramadan fast, with them, and we are grateful for their hospitality.

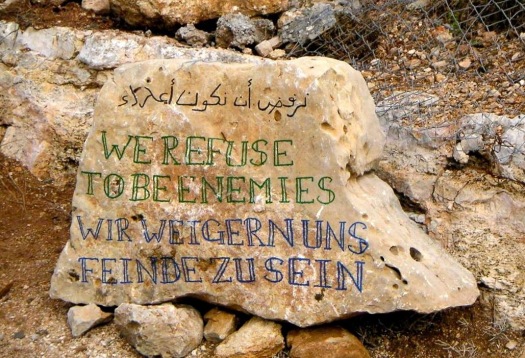

What unites all of these stories and many others we heard is the families’ conviction that staying put is worth it. The occupation has made their daily lives difficult, and they could let the difficulties drive them out. They choose to stay, however, and view the simple acts of daily lives in their homes as their own contribution to nonviolent resistance on behalf of their people. Capturing the spirit of their lives is the tree that Amal Nassar told us about at Tent of Nations. The bulldozers left one fig tree standing in the middle of the grove and they have named the tree “Sumud” or “steadfastness.” At the entrance to the Tent of Nations stands a rock with these words inscribed in three languages: “We refuse to be enemies.”