Protest. All it means is to disapprove or object to something. Yet the word carries so much baggage, it seems downright inflammatory sometimes. I served on a local panel of women who had attended the Women’s March in Washington in January. The moderator asked if anyone had any concerns now that they were back home again. One woman spoke up with considerable energy about how the media had characterized those who marched as “protesters.” No, she insisted, we weren’t protesters. We weren’t angry. We were peaceful. We had a positive message. Several others on the panel strongly agreed.

“The lady doth protest too much, methinks,” as Queen Gertrude says in Hamlet. This woman’s protest of protest brings us right to the core issue: many Americans are afraid to express their disapproval or objection to what their leaders do or say.

Europeans have been quicker to pour a million or more citizens into their streets when their leaders misuse their power, but we Americans relish a sort of exceptionalism about ourselves. Let’s be polite and patient, and perhaps the leaders of our storybook democracy will save us in the end.

Whatever we call this exercise in free speech, all of the women on the panel had been drawn to travel across three states to speak out plainly in our nation’s capital on the side of justice. It was something to celebrate.

My activist group, People for Peace & Justice Sandusky County, has been protesting war and social injustice at a downtown Fremont corner every week since 2007. Friends sometimes ask me why we do this thing that seems so futile. What can it accomplish?

My favorite answer is that we are telling passers-by that it is legitimate to dissent. Each of us has a right to decide whether or not to consent to the dominant political ideology. Members of the public are not unanimous in their views. We hope we can give passers-by the courage of their convictions, and at the same time find our own.

A few years ago, I wrote an article for Toledo Faith and Values that attempted to express all of this. I offer it, slightly updated, below.

Shattering the Unanimity of Consent

Josie Setzler | Original version published by Toledo Faith and Values | Sep 4, 2012

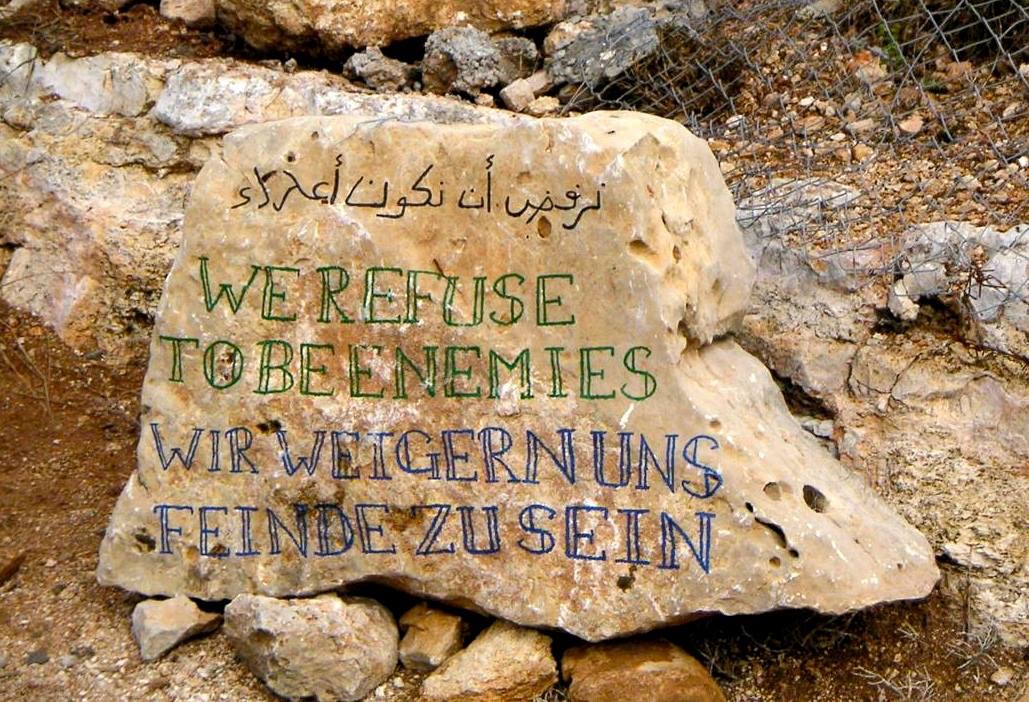

There can be great urgency in protest’s seeming futility. Pietro Spina, the hero of the novel, Bread and Wine, felt that urgency. Pietro does just one thing during a time of war; he goes out in the night and writes the word NO on the town walls. Writer Robert Ellsberg comments, “If nothing else, his deed shatters the ‘unanimity of consent’; it allows people to envision the subversive possibility of an alternative reality.”

Saying no feels plenty futile. I’m one of the Sandusky County residents who gather at a busy downtown corner in Fremont every week to say no to war. We’ve done this for some nine years now and we don’t expect the world will give us an excuse to stop anytime soon. Nonetheless I feel the urgency of saying no.

The “unanimity of consent” pervades and supports the comforts of my daily life that have been bought with the application of immense US military might. It’s convenient to turn a blind eye to the suffering caused elsewhere, and life’s daily busy-ness serves well to distract us. It seems as if every week the news gives us another story of innocents killed, drones hovering menacingly over houses in tiny villages, men tortured, people incarcerated without charge, our own citizens surveilled, but then the stories pass into oblivion. And my life goes on as always, just like the lives of all the drivers passing by me at the corner of State and Front.

I’m complicit until I find a way to say no, to break the unanimity of consent. In small ways, consent starts to break up once someone says no. Long-time Chicago peace activist Kathy Kelly tells us we need to “catch courage” from each other. I’ve found the process is mutual for motorists and protesters alike. My husband Denny holds the sign that lets people make their own statement. “Honk 4 Peace,” it proclaims boldly. He pumps the sign up and down strategically as the light turns, and the honking begins. The honks crescendo beautifully and our spirits soar. Some folks whose horns don’t work gesture in frustration at Denny. He grins and tells them to turn on their windshield wipers. They are delighted to comply, and we laugh in solidarity.

I admit there’s something foolish about facing traffic with a sign announcing my wisdom in just a half dozen words. I remember a conversation with my friend Jude who called our signs ineffective, because “you don’t have room to make an argument on a sign.” With a master’s degree in theology, Jude figured a statement is a thesis that needs arguments to defend it. I knew I liked to argue with the best of them, but the vigils gave me something else. “Jude, just making the statement is the whole point,” I told her. “It’s about finding the courage of our convictions.” People fear they’re not allowed to dissent, let alone express that dissent. They see someone they know standing on a street corner in their own hometown expressing what they know deep in their own hearts, and they are surprised. The protester finds the courage of her convictions in the hopes that passers-by might discover that same courage in themselves.

Yes, there are the occasional obscene gestures and angry shouts. My friends at a longstanding vigil in Tiffin actually got mooned once by a passing motorist. We’ve learned that we are not there to change the minds of people who disagree with us. We are aiming instead for the hearts of those who wonder about these things.

Don’t judge your action by its prospect for success, long-time peace activist Father Daniel Berrigan told his Toledo audience back in 2002 as he spoke about activism in the run up to the Iraq War. An audience member asked him why our religious leaders were not speaking out at the time. “You can’t wait for them,” he told us. “It’s up to you. Do it. Get going.”

Speaking out is the job of each of us. That much we can do right now. Fellow protester Tom Younker tells me as we wave at passing motorists, “I stand here now, because I didn’t do it when the Vietnam War was raging.” He senses it is not too late, and so we’ll be out there with him again next week. We welcome others to stand with us wherever they might be.

–Josie Setzler | March 24, 2017